“It’s one of the best feelings in the world to find your vocation, and Rauschenberg never lost the illuminating joy that came with that discovery…” – Hilton Als, “Robert Rauschenberg’s Art of the Real”, The New Yorker

At some point in the future, the artist Ed Ruscha (b. 1937) will die and I will read obituaries and feel the urge to also write about what he means to me—more, clearly, than any journalist who’s tasked with the work. So to get ahead of that, I will start now.

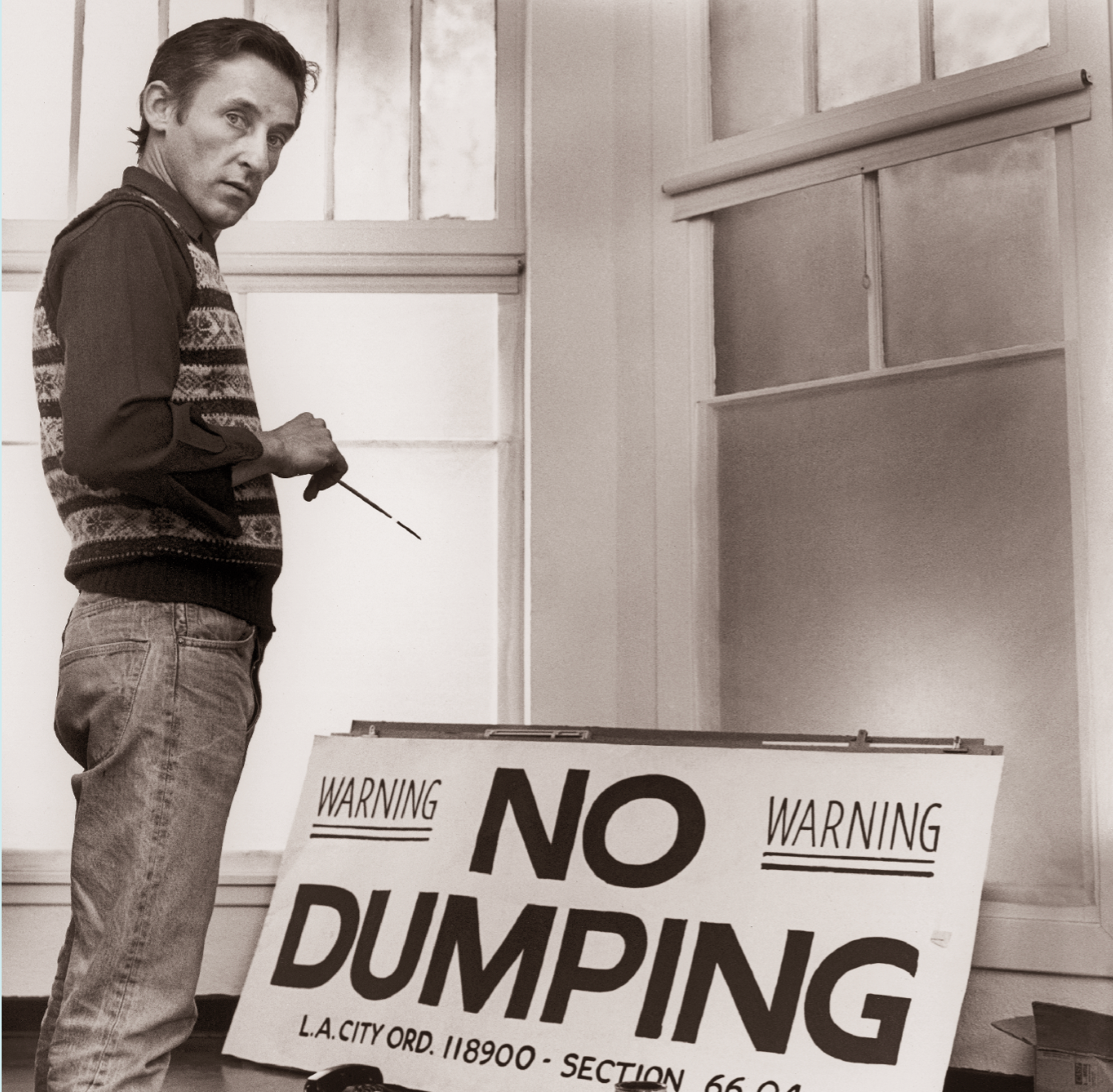

L: Me in my shed, self-portrait, 2025, after James Wojcik, ca. 1981; R: James Wojcik, Ed Ruscha at 1024 ¾ North Western Ave, Hollywood, ca. 1981

If I may add to Als’ quote above: One of the best feelings in the world is to find a person who pays attention to the same things you do. In Ruscha, I found an artist whose mind seems to spark at the same small pleasures and objects of life: text separated from context; conceptual collections of vernacular systems, places, and objects; painstaking reproductions of notable aspects of the built and designed environment. Ruscha’s work has found its audience, obviously, but I often feel as if he were talking just to me. A metaphor: If a million people looked at a cityscape and saw the tallest skyscraper, Ed and I would point at the same window and what we could both see through the open curtains.

I didn’t realize that being an artist meant, at the most basic level, making choices. I didn’t see value in what I saw or noticed, or what I was moved to create until I found Ruscha’s work, whose collection of “Thirtyfour Parking Lots” (1967) sets my heart aflutter. I didn’t know that people didn’t see what I saw when I looked at a thing—I didn’t realize that being an artist, at another most basic level, means paying attention to what and how you see.

It has been 20 years since I uncovered this connection with Ruscha’s work. And now that I have discovered (we hope) my vocation, it’s a staggering feeling to realize that deep down I’ve known my vocation for that many years too. I have worked at art museums and tried out graphic design and now I’ve arrived at sign painting—he has helped triangulate the wanderings of my aeshetic life into something that can be formed. I am working on what that formation is now. I have stolen his ideas, knowingly; some highschool-era work predated my knowledge of his existence. I will continue to steal from his oeuvre.

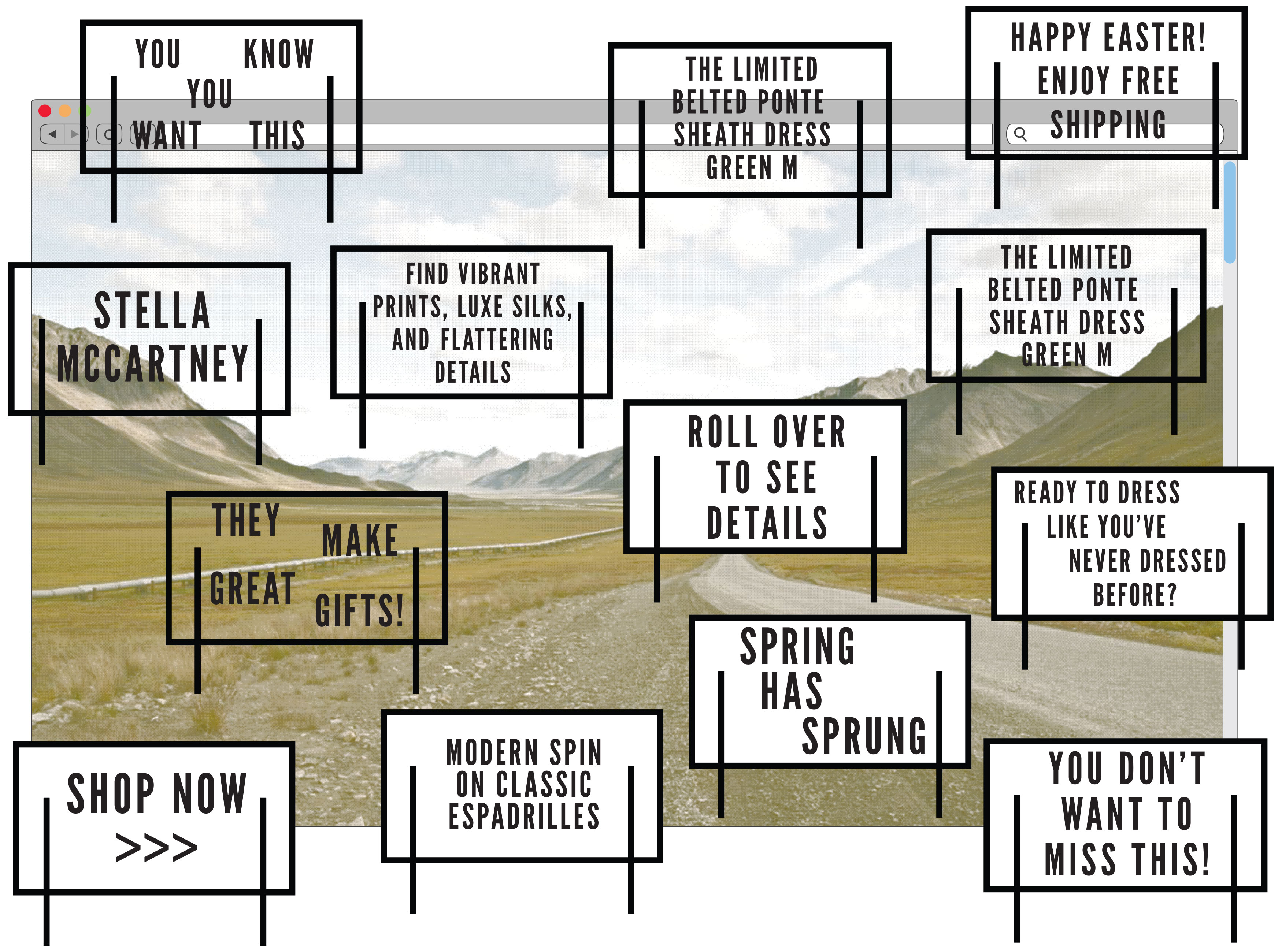

L: Ed Ruscha, Lonely Highway, 2019; R: Kristina Fong, Landscape Piece, 2014

Sign painting is a craft, but in Ruscha’s hands, it’s conceptual art. Ruscha notices signs (he admits as much in his forward to Sign Painters: The Book.) Think of the Hollywood sign as the most obvious, then the apartment names on every building on the Sunset Strip, and the 12-year gap between Blue Collar Tool + Die (1992) and The Old Tool + Die Building (2004).

This is the direction I’m heading, for now.

— Version 1, December 2025